|

Often when we partake in certain activities or behaviours, instead of exercising or doing other things we promised ourselves we would do, we just do it without questioning why. As a result we may experience a variety of emotions (guilt, disappointment, anger etc.) all of which will vary in intensity depending on what we did or didn't do. For example you may feel mild guilt when you miss one exercise session, or you might experience major guilt or even anger when you miss a whole week’s exercise or have several junk food binges.

At the point when we make the choice to not exercise or not stick to a diet, we usually don't think about the logic of what we are doing, instead opting to embrace the emotional rewards or benefits of the ‘black listed’ behaviour. For example, despite saying to yourself “I should be exercising”, the thought of sitting on the couch with a beer is more emotionally appealing at that point in time. Once you have the idea in your head you often don't consider the negative consequences, choosing instead to let your thinking run away with thoughts of how good the beer will taste and how relaxed you will feel.

0 Comments

An incentive may be defined as an external reward or stimulus. An incentive has the capacity to motivate us to think, behave and act in a specific way. This incentive can be something tangible like money, or intangible, like a good feeling. An incentive doesn't guarantee that a person will become motivated, only that it has the potential to motivate. As discussed previously, motivation means different things to different people. This means an incentive that could motivate one person may not necessarily motivate another. This is due to the fact that we all think differently and believe in different things. This results in the value of incentives varying between individuals.

Earlier in this series we established that many motivational theories consist of both biological motivators (nature) and environmental motivators (nurture). When considering incentive theory we begin to see a shift away from biological influences and a movement towards the environment and its influence on behaviour. While instinct theory and drive theory draw almost exclusively from biological motivators, incentive theory is the opposite in that it draws on environmental motivators. Incentive theory is based on the idea that a positive external stimulus attracts or pulls a person in a certain direction. This is the opposite of both instinct and drive theory, where a negative internal state, e.g. hunger, pushes you in a certain direction. There are several variations of drive theory. At the core of all of these theories is the idea that all organisms, humans included, continually attempt to maintain homeostasis or a state of physiological equilibrium.

The theory states that all organisms experience internal tensions and pressures called drives. These drives then motivate us to engage in activities that aim to reduce the tension. Take hunger as a drive. This is one example of a biological drive that leads to physical discomfort - which leads to the motivation to get food - which leads to eating - which leads to a reduction in physical tension, thus reducing the drive. This process leads to the restoration of equilibrium where the process will begin again. Temperature is another example of a biological drive. We have a homeostatic temperature of 37 degrees Celsius (98.6 degrees Fahrenheit). When we experience hot or cold we automatically respond by perspiring or shivering. We are motivated to reduce the drive, which in this case is the feeling of being too hot or too cold. Instinct theory states that motivation is the product of biological, genetic programming. Consequently the theory proposes that we are all driven by the same motives as per our evolutionary programming. As a species, our behaviours and the drivers of these behaviours, are innate. As a result all of our actions are essentially instinctual.

It is the collective motivation to survive that is fundamental to this perspective. Because we are all genetically 99.9% the same, all of our motivations and drives are derived from the same instinctual programming. For example, instinct theory proposes that parents don't play that big of a role in the development of their children. Consider a mother staying awake all night with her crying infant in an attempt to provide comfort. Instinct theory states that this is done for no other reason than the mother being programmed to behave this way. The theory would not attribute this behaviour to wisdom, or habituation, or being brought up in a specific way. Nor would having strong or weak female role models or anything else other than pure biology. Issues arise with this perspective when considering that not all instincts are universal. Many theorists believe that instincts are subjective and are governed by individuals and their differences. Moreover not all people exhibit the same attachment levels or behave in the same way. In this blog series, ‘Motivational theories’, we will be taking a look at a selection of perspectives and theories on motivation in an attempt to understand why we do the things we do. Where possible and/or relevant, links to exercise, health and fitness will be made. The following theories will be covered:

Before taking a closer look at the first theory (instinct theory) lets first consider the following “why” questions…

There is a simple answer to each one of these questions. That answer is MOTIVE. You see, YOU NEVER JUST DO SOMETHING FOR THE SAKE OF IT. Although it may feel as though you sometimes do things for no apparent reason there is actually a motive behind every behaviour or action you carry out. Is salt really that bad for us? The advice that salt is bad for us and we should limit how much of it we should eat is on of the key public health messages today. The Ministry of Health, the Cancer Society, the New Zealand Nutrition Foundation and the New Zealand Stroke Foundation all give clear and unambiguous advice that eating too much salt can cause high blood pressure and increase the risk of heart disease, heart attacks, strokes, kidney disease, stomach cancer and osteoporosis. In the US the director for the Center of Disease Control (CDC) and prevention has gone so far as to say that reducing how much salt you eat is as important to your long term health as giving up smoking. But does this science behind all of these claims stack up? Gary Taubes, journalist and award winning of 'Why we get fat' (2011), and 'Good calories, Bad calories' (2007) doesn't think so. Listen to this fascinating interview below.

Realistic. The fourth term examines whether both your goals and the plans you created to achieve these goals are realistic. In other words “is my goal do-able?”, “is my action plan to achieve this goal do-able?”, and “do I have the skill set or knowledge base to follow through on my plan?”

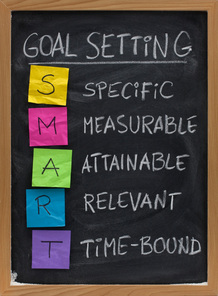

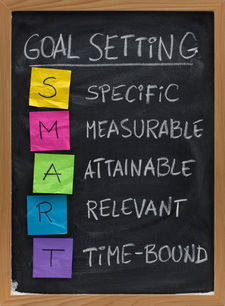

To put this into perspective, consider the goal “I want to lose 5kgs in three months.” While this goal may sound realistic the plan you put into place to achieve it may involve unrealistic methods, like going cold turkey on certain foods or starving yourself. Hence although this goal is realistic the plan isn't. Timing is another issue that needs to be considered. You may have a specific, measurable, achievable goal in place but you may also be too busy doing other things at the time. As a result trying to achieve this goal, at this point in time, would be unrealistic. Realistic is the one term of the SMART method that I really agree with. How realistic something is to achieve will directly relate to the probability of you achieving it. However deciding on whether a goal is realistic can be tough. There is no one way or blanket approach to use when making this call. It is something that is very personal and can’t be quantified due to the huge variation of factors involved. Therefore when considering how realistic a goal may or may not be, make sure you think about the ‘you’ factor. That is, how realistic is it that ‘you’ can achieve this goal and not how realistic is it that this goal can be achieved. Assuming you have established that exercising is of significant importance, how should you go about setting goals? The SMART goal approach, which stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timely (or Time Based) is one way of looking at the process of goal setting. Although I find some of these terms more useful than others, all five are relevant pieces of the goal-setting puzzle. Let’s take a closer look at each point and explore the strengths and limitations of each.

Specific. The first term states that goals should be straightforward and that they should emphasise exactly what you want to happen. The idea is that the more specific the goal, the more you can focus your efforts and be clear about what you intend to do. For example, setting a goal to ‘do more exercise’ is vague and leaves a lot of room for interpretation and possible avoidance. A similar but far more specific goal might be to ‘go for a 30min walk straight after work every Wednesday and Friday.’ As you can see this second goal leaves little to chance as it clearly states the ‘what’ (a 30min walk) and the ‘when’ (straight after work on Wednesday and Friday). Limitations with specificity arise when your situation or thinking changes, which is often. What happens if you were to injure your foot, or Wednesday night is no longer a viable time to walk, or for that matter you decide you don’t actually like walking? Do you then set another goal? What flow on affect does this then have on the remaining terms of the SMART acronym? How many of us actually understand calories? When it comes to understanding calories many of us can be our own worst enemies. This is exacerbated by a food marketing designed to encourage us to eat more and a political system that does little to stop it. Dr Marion Nestle is a globally recognised expert in nutrition, food studies and public health and also a professor at New York university. In this radio interview Dr Nestle talks about her new book 'Why calories count: From science to politics' (co authored with Malden Nesheim) and explains what calories are, how they affect the body and why its so easy to eat more of them than we actually need.

Increasingly research is identifying that the expectations you have about specific behaviours (what you think you will get out of a behaviour) are what you should be focusing on if you want to make changes.

Often when we do things that we don’t really want to do e.g. overeating, not exercising, drinking etc., it's usually our self talk around expectations that are to blame. Take overeating for example. Expectancy prior to overeating might sound like… 'this (extra food) will make me feel good', 'I need more food', 'it will taste so good', etc. Typically what happens after overeating, assuming it was something you didn't want to do, is that the outcome will be the opposite of the initial expectations. In this case you might now be thinking, 'I feel bad/guilty/angry I ate that', 'I didn't actually need to eat that', and 'it didn't even taste that good'. |

AuthorMatt Williams Archives

December 2015

Categories

All

|

|

Exercise Change© 2011-2022 ● exercisechange@gmail.com ● 021 107 1270 ● (int) +64 21 107 1270

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed